Brooklyn Museum’s Disguise: Masks and Global African Art exhibition

When W.E.B. Dubois advanced the "life behind the veil” and “double consciousness” concepts in The Souls of Black Folk (1903), he was referring to African American experiences of separation and invisibility that also characterize the act of masking. In his poem, “We Wear the Mask,” Paul Laurence Dunbar graphically described the tradition of masquerade in African Diasporic life:

We wear the mask that grins and lies/It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,—/This debt we pay to human guile;/With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,/And mouth with myriad subtleties./Why should the world be over-wise,/In counting all our tears and sighs?/Nay, let them only see us, while/ We wear the mask....(Excerpt from "We Wear The Mask" from Dunbar's Lyrics of Lowly Life (1896).

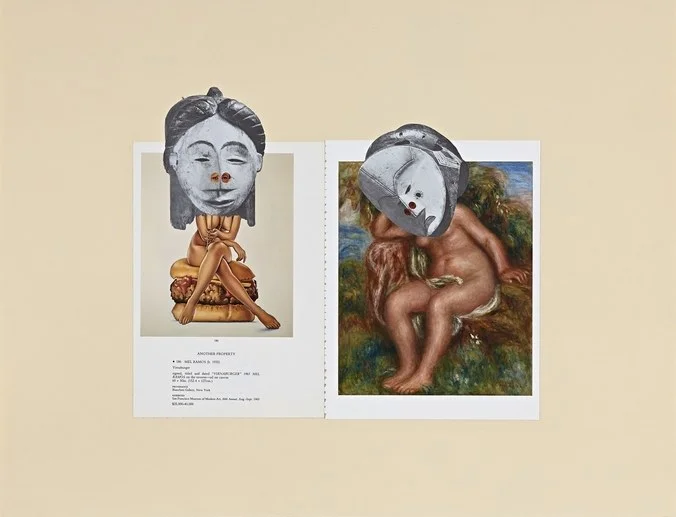

This poem is noted as an inspiration for Sam Vernon, one of 25 contemporary artists represented in the Brooklyn Museum’s Disguise: Masks and Global African Art exhibition, currently on view through September 18, 2016.

Originally organized by the Seattle Art Museum, the exhibition in its Brooklyn iteration includes more than 25 additional works from the museum’s collection of historical art. Classical masks on display (the earliest date to the mid 1800s) represent a variety of ethnic groups and regions on the continent and are made by mostly unidentifiable artists.

The contemporary artists featured in the exhibition are Leonce Raphael Agbodjélou (Benin), Nick Cave (U.S.), Edson Chagas (Angola), Steven Cohen (South Africa/France), Willie Cole (U.S.), Jakob Dwight (U.S.), Hasan and Husain Essop (South Africa), Brendan Fernandes (Kenya/Canada/U.S.), Alejandro Guzman (Puerto Rico),

Gerald Machona (Zimbabwe), Nandipha Mntambo (South Africa), Jean-Claude Moschetti (France/Benin), Toyin Ojih Odutola (U.S.), Emeka Ogboh (Nigeria), Wura-Natasha Ogunji (U.S./Nigeria), Walter Oltmann (South Africa), Sondra R. Perry (U.S.), Jacolby Satterwhite (U.S.), Paul Anthony Smith (Jamaica/U.S.), Adejoke Tugbiyele (U.S./Nigeria), Iké Udé (U.S./Nigeria), Sam Vernon (U.S.), William Villalongo (U.S.), Zina Saro-Wiwa (U.S./U.K./Nigeria), and Saya Woolfalk (U.S.).

These various forms — classical masks, the contemporary art on view, masquerade in a larger context, and the expression of writers like Dubois and Dunbar — all raise questions of individual and communal agency. Who has a choice (literally and figuratively) about when, where and how to perform masquerade?

In this exhibition several artists disrupt and subvert the power dynamics of traditional masquerade. For example, artists Zina Saro-Wiwa, Wura-Natasha Ogunji, and Alejandro Guzman all perform traditionally male masquerades from a female view.

The overall exhibition examines masks and masquerade from a macro level through categorical groupings. “BECOMING Artifacts” displays a selection of classical masks addressing the objecthood of historical items taken out of context. “BECOMING Another Body” looks at masks in a performance context. “BECOMING Controlled” examines masks as a function of social control. “BECOMING Another” addresses empathy, and what it is like to walk in another’s shoes. “BECOMING Again” deals with the re-invention of masquerade in response to contemporary issues. “BECOMING Political” presents masks as tools of critique. And finally, “BECOMING New” looks to the future and innovation via new masks.

The exhibition’s mix of sculpture, photography, performance, video, digital media, sound and installation art creates an exquisitely immersive environment that inspires awe at every turn. The dialectic between classical work and contemporary art invigorates the senses and compliments the conceptual rigor of much of the newer work.

A contemporary flashpoint that stands out in several bodies of work in the show is an exploration of gender fluidity in specific cultural contexts, some real and some imagined. These artists navigate, disrupt, subvert and intervene in gendered terrain in the streets of Lagos, Nigeria, the imaginative space of gender specific secret societies, and in the colonial past.

Alejandro Guzman’s The Fatalist, is one of the first contemporary works near the entrance to the exhibition. It is a sculptural performance object that can function simultaneously as a costume, altar, and moving sculpture. The work was originally performed with a companion, and was made in communion with the Vejigante masquerade tradition in Puerto Rico and the Yoruban deity, Obatala, the Creator.

The life size structure contains textural variety, strong graphic elements, and a pleasing asymmetry that coalesces in a uniquely balanced hybridity. Touches of textile trimming, shells, pink paint, wood, wire, white cloth, geometric sky blue cutouts, fur, rose colored glitter, horns and assorted other materials comprise its exterior.

In Puerto Rico, the Vejigante is typically performed by men. As a subversive commentary on this gendered dynamic, Guzman noted in an email that heembodies The Fatalist as a female spirit in his sculptural performance to reflect his embrace of matriarchal power structures. Formally, this position is symbolically reflected in the The Fatalist’s mirrored belly which is constructed in a reticulated form. The form suggests a dynamic receptive approach to the self and universe typically associated with concepts of the feminine.

A grouping ofNandipha Mntambo’s photography and sculpture visually revolves around the mythology of bulls. Riffing on Greek mythology and traditional Spanish bullfighting, Mntambo re-imagines ownership of masculine and feminine performative space and beyond.

In the photographic series, Praça de Touros (Bullring), shot at an old bullfighting ring in Mozambique, a former Portuguese colony, Nandipha Mntambo dons the costume of a bullfighter and regally performs her role with a powerful embodiment of her character.

In the works, Europa and Sengifkile (Now I’m Here), a photograph and a sculpture, Mntambo explores the animalistic side of humanity through creating and inhabiting a being who is half-bull and half-woman.

Her bodily gestures frozen in sculpted poses reveal her absorption in the experience through small cues, such as a strong grip on her red bullfighting cloth, erect legs, advancing shoulders and piercing eyes that resonate beyond the 2D plane of her photographs.

Exhibition wall text includes this comment from Mntambo: “It’s so easy to separate the binaries of attraction/repulsion, male/female, animal/human, myth/reality, black/white, Africa/Europe, but my fascination is with the in-between space and how it leads to understanding the world in a more global way.”

Saya Woolfalk’s piece, ChimaTEK: Virtual Chimeric Space, encapsulates a large cordoned off space at the center of the exhibition. The dimly lit area is an immersive futuristic wonderland filled with sculpture, textiles, video, futuristic beings and digital media.

However, Woolfalk’s playful colorful installation belies a supremely forward-thinking realm of possibility for global humanity, grounded in empathy. The work follows up on two previous projects that Woolfalk describes in wall text, the first of which was, “...a future constructed for the investigation of human possibilities and impossibilities. It features configurations of biology, sociality, race, class, and sexuality.” After which she created, “a science fiction–inspired project about a fictional group of women called Empathics, to explore the process of hybridization.”

ChimaTEK’s narrative revolves around a, “patented system [that] makes our interspecies and intersubjective hybridization available to all.” The work explores blurring psycho-social boundaries in an effort to create universal access to cognitive and cultural consciousnesses. Through her use of color, shape and soundscapes, Woolfalk creates an atmosphere where this seems like a viable possibility, as well as a retort to a preponderance of dystopic takes on the future of humankind.

The work also appears to reference a global array of spiritual thought systems, including the women’s Sande societies of the Mende people, meditation, yoga, chakras and Woolfalk’s two years of folkloric performance study in northern Brazil.

Two artists with work on view in the latter half of the exihibition, Zina Saro-Wiwa and Wura-Natasha Ogunji, infiltrate masquerade styles that are traditionally male.

Saro-Wiwa engages the Ogele masquerade tradition of Ogoniland in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, her region of origin. And, Ogunji performs Egungun in the streets of Lagos, Nigeria’s capital.

Saro-Wiwa’s motivation for creating an all female masquerade group, commissioning her own mask, and creating photographs and video work about it, appears to be three-fold. One reason is political and simply put: “Ogele masquerade is dominated by men,” she says. Another is personal — her “desire to penetrate this secretive world of men.” She also wanted to “explore the utility of masquerade as a strategy for catharsis.”

In her series of photographs, Men of the Ogele: The Whirlwind Series, Saro-Wiwa documents male masquerade dancers in intimate relation to their photographer. The outdoor portrait-style images — UV prints on aluminum — vibrate through a muted jewel tone palette. Saro-Wiwa’s access to the group was undoubtedly in part due to the Ogoni communities reverence for her late father, internationally acclaimed and beloved human rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa.

The series accompanies a triptych video piece and photographic documentation of Saro-Wiwa’s commissioned mask, Invisible Man. Both are meditations on loss, mourning, anger and the space in between a face and a mask.

In contrast to Saro-Wiwa’s reflections on interiority, Wura-Natasha Ogunji’s An Ancestor Takes a Photograph and Will I Still Carry Water When I Am a Dead Woman?, loudly claim a woman’s space in secret society territory traditionally forbidden to women.

Through Street Egungun and Futuristic Egungun performance interventions in the streets of Lagos, Ogunji seems to engage both feminist leanings and the timelessness of spiritual reality. These interpretations expand upon traditional egungun costumes which connect the Yoruba people with the spirits of departed ancestors.

Photographs that document and capture the energy of Ogunji’s masquerader’s movement through the city echo not only the power of female subversion, but also the masquerade’s function of concealing personal identity to enable the wearer to transcend it and other aspects of the physical realm.

The camera angles and vitality of the photographic performance stills on view and Ogunji’s actual Street Egungun costumes seem to carry an unapologetic embrace of tradition and a contemporary claiming of female self-actualization.

There is a bounty of wonder filled work in Disguise: Masks and Global African Art. The re-organization and augmentation of the exhibition by the Brooklyn Museum’s curatorial team enhances the depth of the contemporary work and provides an increased understanding of the incredibly creative and meaningful continuum of masquerade in the human experience.

- Diana McClure